How to Determine Production Methods

Press molded ceramics were formed by pressing sheets of clay into molds. Separate pieces of the mold were then connected and the seams in the clay joined and smoothed.

Slip casting was made when a liquid clay slip was poured into the plaster mold. After the clay closest to the mold had dried, the excess liquid slip was poured away. The dried clay pieces were removed from the molds, trimmed and joined to form vessels.

To easily tell the difference in vessels created by these two manufacturing techniques, look at the vessel interior. A press molded ceramic will have a smooth or relatively smooth interior, while the interior of a slip cast vessel will follow the relief design on the exterior.

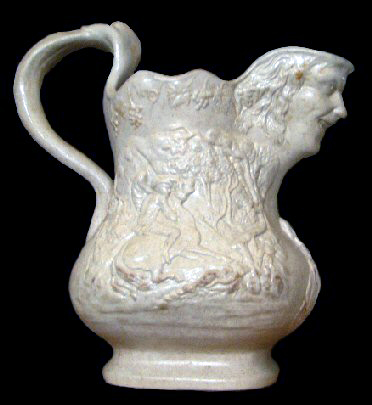

The jug shown at left depicts the Tam O’Shanter pattern,

based on a famous poem by Scottish poet Robert Burns. Impressed in the

base of the jug are the words “Published by W. Ridgway & Co.,

Hanley, October 1st, 1835”. The designs on the jug were based on

a series of engravings by Thomas Landseer for the 1830 edition of Tam

O’Shanter (Henrywood 1984:66). This jug, whose shape is characteristic

of the earliest press molded jugs, was recovered from 18BC27, the site

of the Federal Reserve Bank in Baltimore. It had been deposited in a circular

brick-lined privy along with a number of other ceramic and glass vessels

that suggested the privy had been filled sometime between 1835 and 1870.

Decorative Motifs on Molded Jugs

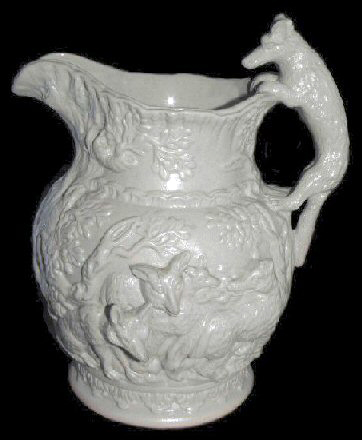

1830s and 1840s – Representative of Hunting

and tavern scenes and mythological themes in deeply molded relief.

Often the lips and handles are elaborately molded to represent human faces,

dogs or other animals, or plants.

Fox and Hounds, c. 1831 (Minton)

(private collection)

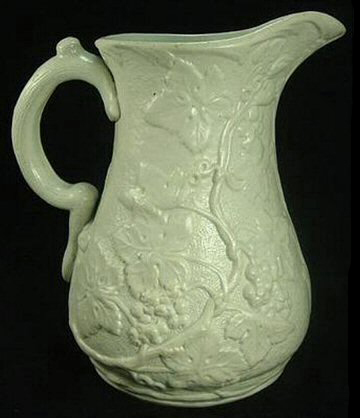

Boar and Stag Hunt, c. 1845 (Masons)

(private collection)

Robert Burns, c.1834 (Machin & Potts)

(private collection)

Jousting Jug, A William Ridgway, Son & Co.

7.5in (19cm) high.

(private collection)

Medieval Revelry (Minton & Co.)

Pattern registered 7-23-1852

(private collection)

Souter Johnnie jug, in buff stoneware.

c. 1830-50, 9.75in (24.6cm) high.

(private collection)

1840s and 1850s – Putti or cherubs.

c.1831-35 Minton Putti

(private collection)

(Private Collection)

Dancing Amorini, 1845 (Minton).

Registered March 20, 1845

(private collection)

Dancing Putti

(Private Collection)

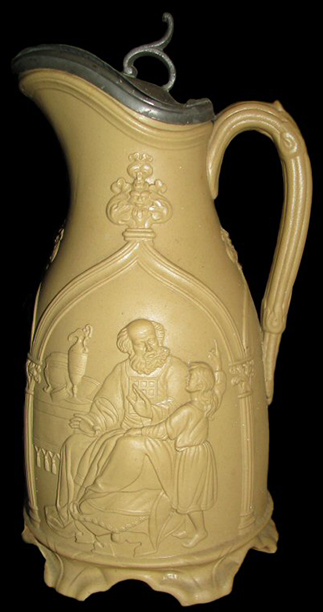

1840s and 1850s – Pattern typical of Genre scenes, including

countryside activities

such as harvesting crops, making wine or sleeping children.

Babes in the Woods - c. 1845

(Samual Alcock & Co.)

(private collection)

Babes in the Woods - c. 1845

(Samual Alcock & Co.)

(private collection)

Gipsey, 1842

(Jones and Walley)

(private collection)

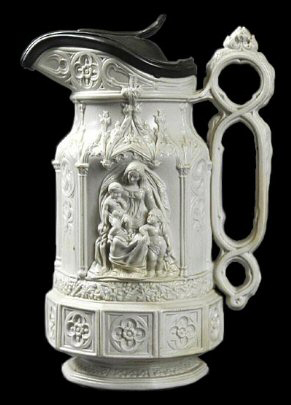

1840s – Religious themes began to appear.

Minster, 1846 and Apostle, 1842

(both by

Charles Meigh)

(private collection)

Infant Samuel 1848

(T & R Boote)

(private collection)

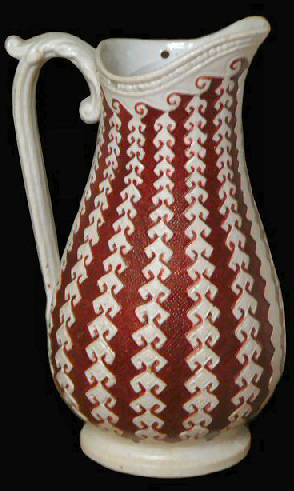

Late 1860s – Geometric and Greek Revival designs begin to appear.

Teapot in a yellow paste stoneware with molded grape motif.

Smear glazed exterior and clear lead glazed interior.

Hanley - Collected by George L. Miller in 1986 in Hanley.

Produced by Ridgway & Abington.

1860s Greek Key design

(W.B. Cobridge)

(private collection)

(private collection)

(private collection)

(private collection)

Floral Pattern Motif Examples

1830s-1840s—Running Plants. The earliest

plant designs were those whose branches,

leaves and flowers were irregularly scattered across the vessel.

Convolvulus, 1848

(W. T. Copeland)

(private collection)

Fuschia -1857

(Ridgway & Abington)

(private collection)

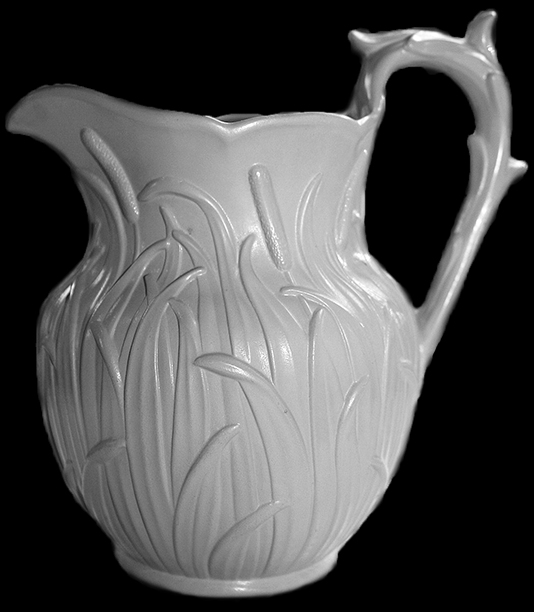

Late 1840s—Growing Plants. Plants took on a more realistic

growth pattern,

springing vertically up the sides of the jug from the base.

Bullrushes, 1848

(Ridgway & Abingdon)

(private collection)

Bullrushes Maker's mark.

Exterior smear glaze and clear lead glaze interior.

Registered by Ridgway & Abington on March 7, 1848.

Hanley -

collected by George L. Miller in 1986 in Hanley.

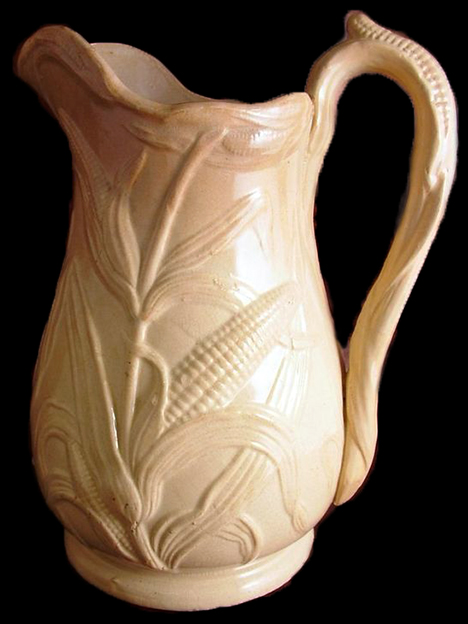

c.1850 Victorian Harvest Jug

(private collection)

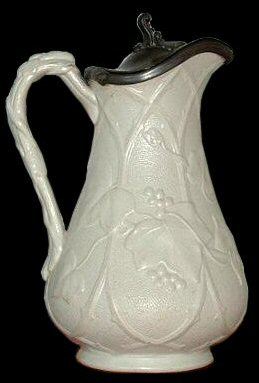

1840s to the 1860s—Naturalistic

Forms. Plants depicted in great detail began to appear,

often shown against an appropriate background; for example, in Mayer’s

Convolvulus pattern,

the jug is molded to represent a tree stump, against which morning glories

grow.

Mayer’s Convolvulus pattern

(private collection)

1850 - Dudson

(private collection)

(private collection)

1853 Niagara Falls Cascade

(private collection)

Mayer’s Convolvulus pattern

(private collection)

1850 - Dudson

(private collection)

(private collection)

1860s-1870s—General Floral. Price competition led to simpler design

and manufacturing standards. Stylized floral patterns, often in conjunction

with geometric designs, began to appear.

Gothic Ivy - 1856

(William Brownfield)

(private collection)

Dudson Brothers - c. 1898

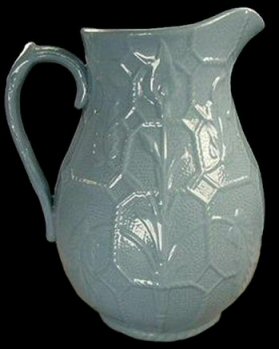

Beginning in the mid-1870s – Japanese-influenced designs of random shapes and sprays of

foliage and flowers, such as cherry or prunus blossoms.

Japanese Sprays - 1877

(Pinder, Bourne &

Co.)

(private collection)

Hanley

Collected by George L. Miller in 1986 in Hanley

Fluted teapot in a greyish green pasted stoneware with smear glaze

on exterior and glazed interior.

Cannot be attributed to a particular manufacturer.

Private Collection

The teapot fragment on left appears to be very similar to the small teapot pictured here. This vessel, standing 3.5” tall, was described as a “one cup” teapot, circa 1830. Note the metal handle attached to replace a broken ceramic handle.

http://andrewbaseman.com/blog/?tag=stoneware&paged=2

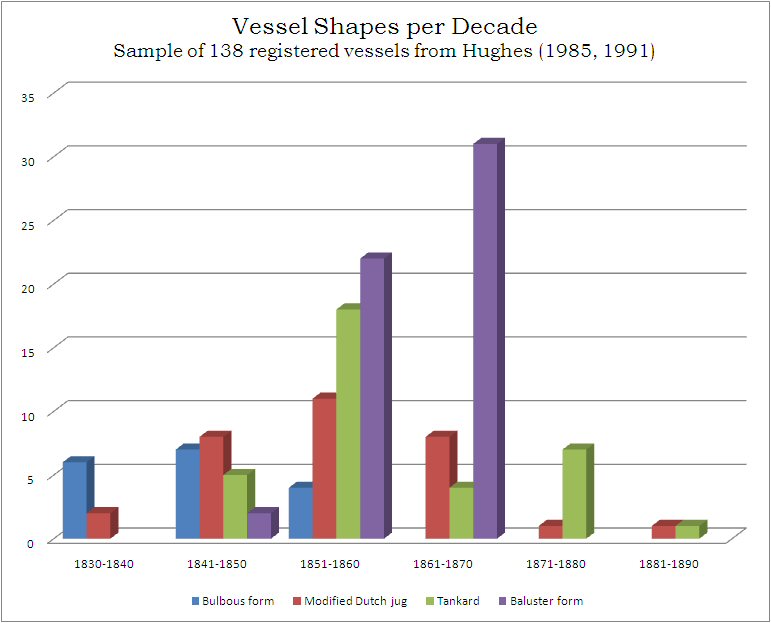

General Vessel Shapes

Vessels are shown without molding for clarity.

Figure - a Figure - b

1830s-1840s— Bulbous Form. A bulbous, low-weighted body was widely used (Figure –a), becoming more slender (Figure –b) in the later 1840s. Generally round in cross-section, these bulbous jugs had pronounced pedestal feet, flaring lips and high, molded handles. Smaller foot rings and lower, less flaring lips appeared in conjunction with the more slender jugs of the late 1840s.

Vessels are shown without molding for clarity

1830s onward—Modified Dutch Jug. Vessels with their center of gravity rising towards the shoulder were present throughout the entire production period, with a brief increase in the number of registered vessels in the late 1840s and early 1850s. Vessel generally displayed small foot rims and lower, less flaring lips.

Vessels are shown without molding for clarity

Beginning in late 1840s—Tankard Form. Characterized by a flat base with simple, straight sides tapering towards the top of the vessel. Tankard-shaped jugs initially continued the use of upward flaring spouts, later replaced by flat rims.

Vessels are shown without molding for clarity

Mid to late 1850s onward—Baluster Form. Beginning around 1850, but increasing later that decade, potters adopted a shape characterized by a spherical lower body on a small footring, tapering continuously to a flaring spout.